The EU’s tariff hike on electric vehicles from China: The data behind the decision

Written by: Anupama Sen

For nearly a decade, China has been the linchpin of global supply chains, thanks to its competitive labour costs and vast manufacturing prowess, earning it a moniker as the ‘factory of the world’. China’s strong manufacturing position extends to the automotive industry. Against that backdrop, starting on 4 July 2024, the EU will implement tariffs, in the form of countervailing duties (CVDs) ranging from 17% to 38%, on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs). These duties on Chinese EV imports will be on top of an existing 10% duty, thereby reaching a peak of 48%. The decision to levy further duties follows an investigation by the European Commission launched in October to investigate Chinese subsidies distorting EV prices and posing unfair competition risks to European carmakers. Thus, the tariffs are applied on a company-specific basis, tailored to the level of subsidies allegedly received by Chinese firms.

The EU’s tariffs on Chinese EVs could be seen as a strategic move aimed at reducing its dependency on China in this sector whilst at the same time stimulating domestic EV production. While some may view this policy as protectionist or neo-mercantilist, it could alternatively be seen as a prudent industrial strategy to foster economic resilience for the EU and to create a level playing field in the global market for EVs. This blog explores the necessity for such a strategy, supported by data illustrating the EU’s growing reliance on Chinese EV imports.

Analysis of Import Data

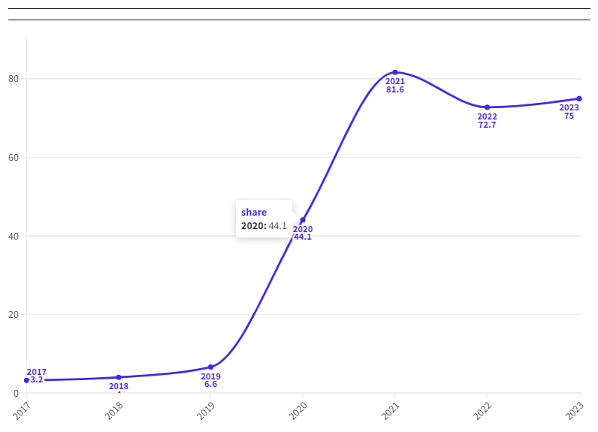

Imports of Chinese produced EVs into the EU market have increased significantly over recent years. Table 1 presents the import values for the car industry and electric vehicles (EVs) from 2017 to 2023, while Figure 1 shows the share of EVs within the total car industry imports. The share of EV’s in total car imports from China rose substantially from 3.2% in 2017 to 81.6% in 2021, with a slight rebound thereafter. While it is difficult to pin down any single specific factor that led to this surge in EV imports in 2021, by then China’s EV industry had grown substantially. This was in part due to substantial state subsidies that enabled manufacturers to offer EVs at competitive prices. Additionally, the EU’s commitment to green energy, including incentives from the 2019 Green Deal, had made the market more receptive to EV imports. Lower trade barriers for Chinese EVs in the EU compared to regions like the U.S. also facilitated this surge. However, EU imports from China have been rising in absolute terms throughout the entire period, in both EVs and non-EVs.

Table 1: Import Value of EVs into EU from China

|

Year |

Car Industry (billion USD) HS 8703 |

Electric Vehicles (billion USD, HS 870380) |

|

2017 |

0.46 |

0.01 |

|

2018 |

0.61 |

0.02 |

|

2019 |

1.02 |

0.07 |

|

2020 |

2.06 |

0.91 |

|

2021 |

7.03 |

5.74 |

|

2022 |

9.94 |

7.23 |

|

2023 |

13.96 |

10.47 |

Source: UN Comtrade

Notes: Figures are in billion USD. HS code 870380 refers to: Motor cars and other motor vehicles principally designed for the transport of <10 persons, incl. station wagons and racing cars, with only electric motor for propulsion (excl. vehicles for travelling on snow and other specially designed vehicles of subheading 8703.10).

Figure 1: Share of EV imports to the EU from China in Total Car Industry

Source: Author’s Calculation on Import data from 2017 to 2021 using UN Comtrade

Tariffs in the changing landscape

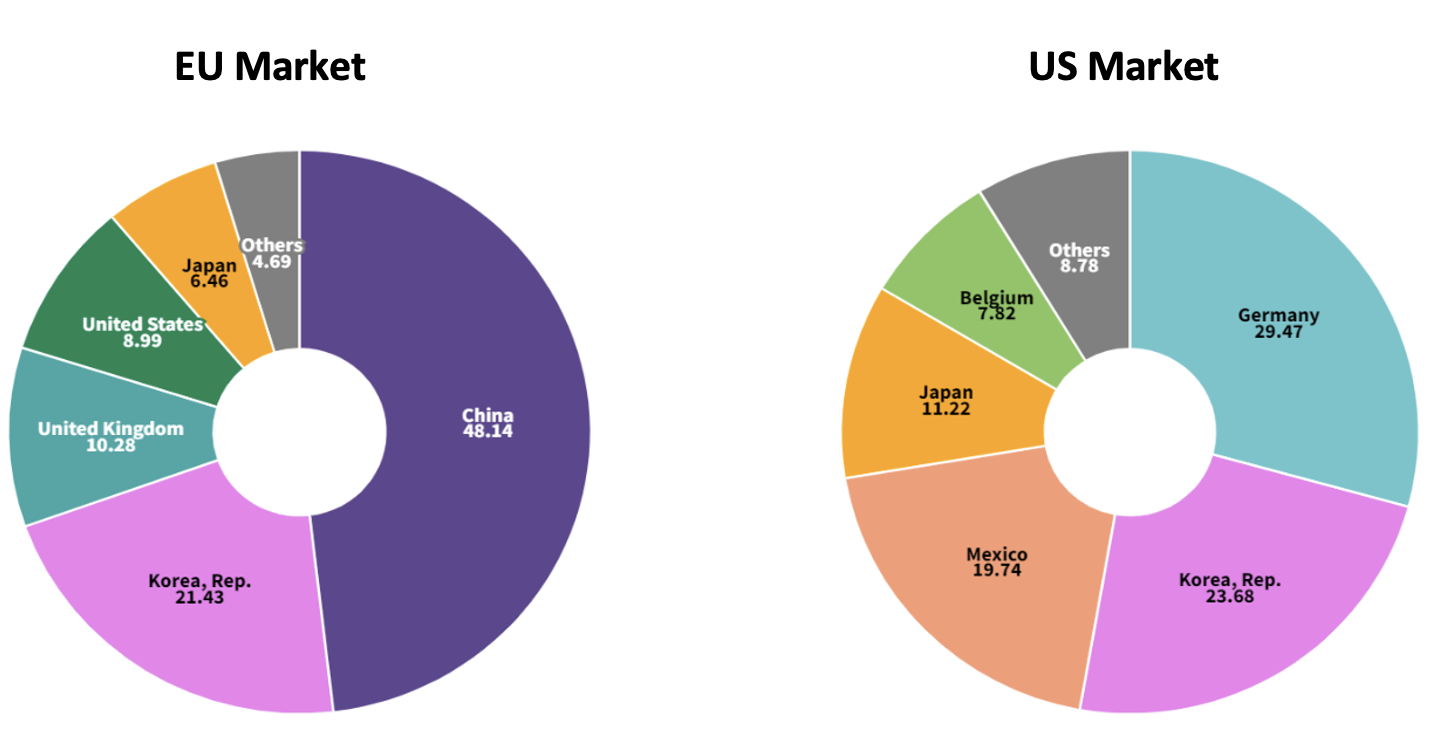

Whereas the EU has implemented tariffs on Chinese EVs in the face of a huge surge in imports, the United States has imposed even higher tariffs of up to 100% on Chinese EV imports despite minimal penetration of these vehicles in its market. Unlike the EU with its heavy reliance on China, the US has diversified its EV supply chain primarily through suppliers in Germany, Korea, and Mexico. This difference underscores how the EU’s approach is potentially consistent with addressing concerns about economic vulnerabilities and promoting local industry growth. In contrast, the US strategy focuses more on safeguarding its existing supply chain diversification.

Figure 2 shows the largest suppliers of EVs to the EU and US markets, respectively. We can observe how heavily reliant the EU is on China as the largest supplier of EVs by a wide margin, whereas the US has been able to diversify its supply chain sufficiently among other exporters.

Figure 2: Top suppliers of Electric Vehicles in 2023, EU and US

Source: Author’s Calculation from UN Comtrade Data

The legal framework behind the differentiated tariffs

Beyond the economic implications, China has complained that the EU duties contravene WTO rules. The WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement) provides the legal framework for these actions, allowing member countries to impose countervailing duties on subsidized imports harming domestic industries. While differentiating duties by firm is common in anti-dumping cases, it is less familiar in the context of subsidies. This differentiation might initially raise concerns about discrimination. Article 15(2) of Regulation (EU) 2016/1037 allows the EU to impose firm-specific countervailing duties. The SCM Agreement’s silence on this practice implies its likely permissibility due to the absence of an express prohibition.

Moreover, the EU’s regulation includes a separate procedure for calculating duties in cases of non-cooperation, potentially resulting in higher tariffs for such firms. Nevertheless, the basis for selecting specific Chinese companies under investigation remains unclear. Chinese firms receive various forms of support, including preferential interest rates, directed credit, tax credits, and cross-subsidies. The methodology for calculating tariffs has only been circulated to the sampled firms thus far. Until the EU publishes its methodology, it is difficult to fully assess the legal validity of the EU’s differentiated tariffs and how subsidies for each firm have been accounted for, as well as the injury to the EU industry caused by each firm.

Potential Impacts and Challenges

Economic Implications

The EU’s tariffs on Chinese EVs will have varied economic repercussions. They may serve as a catalyst for Chinese manufacturers to relocate production to the EU. For instance, Chinese carmaker BYD has established EV plants in Hungary, and Geely has shifted production to Belgium. This shift has the potential to attract investment, bolster local manufacturing, stimulate job creation, and enhance EU technological capabilities.

However, the immediate consequence of higher tariffs could be increased costs for consumers as part of the tariff rise will most likely be passed on to them. In addition, more protection for EU producers might shift their focus away from innovating and seeking efficiency gains. Finally, the tariffs may strain EU-China trade relations and prompt retaliatory measures.

Environmental Considerations

Imposing tariffs on Chinese EVs may also jeopardize the EU’s ambitious climate goals, as outlined in the European Green Deal. Higher tariffs are almost surely set to slow down EV adoption rates in the EU, delaying the transition away from fossil fuel-powered vehicles and hindering progress towards achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Additionally, efforts to boost local EV production in response to tariffs may temporarily raise CO2 emissions during manufacturing, particularly in energy-intensive battery production. Striking a balance between trade policies and environmental objectives is crucial to ensure that measures such as CVDs support rather than hinder the EU’s carbonization progress.

Strategic Diversification

As the US and EU pivot away from heavy reliance on Chinese manufacturing, they are integrating ASEAN nations (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) into their supply networks. These efforts are bolstered by frameworks such as the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)[1]. This strategic shift underscores the imperative of diversifying supply chains to enhance economic resilience amidst global uncertainties.

In this recalibration, cultivating strategic partnerships—often termed friendshoring—takes on critical significance. These alliances aim to deepen economic collaboration while mitigating risks associated with overreliance on single suppliers. As part of such initiatives, the EU may aim at strategically diversifying its EV supply chain by investing in economies such as Mexico, Japan, and South Korea, thereby enhancing supply chain resilience and reducing dependency on China. India, with its burgeoning EV market, represents a significant opportunity. Notably, in 2023, India surpassed China in three-wheeler EV sales, underscoring its potential as a key player in the global EV industry[2].

Conclusion

The EU’s impending tariff hike on Chinese EVs presents a complex challenge touching on economic, environmental, and geopolitical dimensions. While aimed at protecting European industries from unfair competition, these measures may strain EU-China relations and potentially undermine the EU’s climate goals. Balancing the need to diversify supply chains with environmental goals and political costs is crucial to mitigate risks and ensure sustainable economic growth.

[1] Neither the EU nor the US are part of CPTPP, even though the agreement is shaped on the provisions negotiated for the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). This latter was heavily influenced by the US, although it withdrew from it in 2017 and CPTPP came into effect between 11 signatories in 2018. The UK signed an accession protocol in 2023.

[2] https://www.cnbc.com/2024/04/26/india-says-new-ev-policy-will-open-up-market-to-global-players-.html

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.