How much damage could Trump’s tariffs do and what can be done?

Written by: Michael Gasiorek

The short answer to the first part of the question is: “a lot” – and the damage is likely to be both globally and to the US itself. A longer answer is that, in many respects, we do not really know. This is because it is unclear why these US policies are being introduced, whether they may be reversed, and what other policies may be introduced or threatened both by the US as well as by other countries. The short answer to the second part of the question is “not much”. However, a the longer answer would be: it is horribly complicated with so many unknowns, but governments and businesses need to think long term, cooperate and be proactive as opposed to reactive. This is not easy.

At present the policies being introduced against other countries largely amount to threatening to introduce or raise tariffs on goods. If we therefore focus on goods trade in 2023, the United States accounted for just under 14.5% of world imports, and just over 8% of world exports. This means that out of the total world demand for goods being exported, the US buys one-seventh of these and supplies roughly one-twelfth of world exports. Any policies to significantly restrict these trade flows will inevitably have a substantial direct impact on the world economy, and even threatening to do so, even if subsequently withdrawn, will have consequences.

Although the tariffs on Mexico have been suspended, this does not mean that Trump’s policy announcements will not have serious negative repercussions. These could impact not only Mexico but also the US’ trading partners and the US itself.

Then there are other knock-on effects. The impact will be on stock markets and exchange rates in the short run. In the medium to longer run there will be consequences for inflation, economic growth and investment flows for the US, but also globally. Predicting the extent of this, and the direction of changes in investment flows is fraught with difficulty. For example, some investors may shy away from the US market, while others could choose to increase US investments and be protected behind the US tariff ‘shield’.

There is also the impact on the multilateral rules-based world trading system. It is striking how little this issue appears to be discussed among policymakers and commentators. Both China and Canada have indicated they will raise a dispute with the World Trade Organisation in response to the proposed tariffs. However, the WTO is now very weak and it is not even clear whether the retaliatory responses are WTO compatible. It is also unclear where this leaves the free trade agreement between the US, Mexico and Canada (USMCA) – presumably in tatters. The silence on these issues reflects the impunity with which the US is ignoring those multilateral rules and the tacit acceptance of the weakness of those rules by others. This is destabilising and worrying.

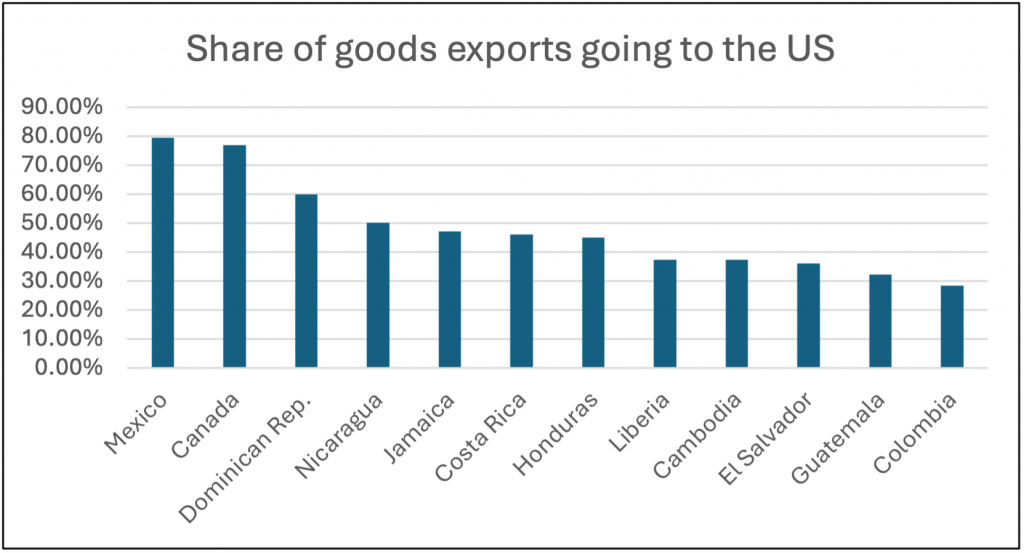

The consequences will vary very widely across countries. The chart below identifies the 15 countries in the world with a population greater than 1M who are most dependent on the US as an export destination:

What is striking is the very high dependence of both Mexican (79%) and Canadian (77%) exports on the US market. For Canada, 32% of its exports to the US are in mineral fuels, followed by vehicles at 14%. For Mexico, 28% of its exports to the US are vehicles and 21% electrical machinery. However, many other sectors are highly dependent on the US market. For Canada, 56 out of a total of 97 industries the US accounts for more than 75% of these industries’ exports. In total these 56 industries account for over 50% of Canadian exports to the US. For Mexico, this is the case for 82 industries accounting for 98% of Mexican exports to the US. If the tariffs go ahead the impacts will be widespread across most sectors in the Canadian and Mexican economies.

Conversely the share of US exports going to Mexico and Canada, is around 15% and 17% respectively. These are also non-negligible shares, although these represent considerably less dependence of the US on Mexico and Canada than vice versa. It is also the case that trade constitutes a much more significant share relative to overall GDP for Canada and Mexico (where it is around 70%), than for the US where it is around 25%.

The US has considerably more economic leverage and the threatened tariffs on Canada and Mexico will have a substantial impact on these countries. Additionally, any retaliation is likely to have a much smaller impact on the US. The figures given here are, of course, averages, and it may be that Canada and Mexico may have more leverage than these figures suggest because of the strategic economic or political importance of certain products or industries – be this oil / energy or critical minerals.

Canada and Mexico are particularly reliant on the US. The impact on other countries – the EU, China, Japan, or the UK for example, is likely to be smaller, and probably also their ability to retaliate and have a significant impact on the US economy. By way of contrast, the share of Chinese, EU, Japanese, and UK exports going to the US in 2023 was approximately 15%, 19%, 20% and 13% respectively.

The bottom line is that President Trump’s policies – enacted or threatened – will very likely have a damaging effect on the world economy, affecting individual countries to varying degrees and, of course, the US itself. The ability of other countries to retaliate with a material effect on the US economy is also somewhat limited, and is thus unlikely to result in a reversal of US policies. Policy reversal is more likely if countries acquiesce to Trump’s demands. Retaliation would also almost certainly further damage the retaliating countries. Just as the Trump tariffs are economically harmful to the US, retaliatory tariffs imposed by partner countries would also hurt their own economies, even if such measures are politically necessary.

Where do we go from here? A key problem in ‘responding’ to this new policy environment is the lack of clarity as to what the new US administration really wants, and the lack of coherence and economic logic in the justifications being made, in particular regarding the supposed egregious nature of bilateral trade deficits. Once uncertainty is introduced it is very hard to reverse. It is like letting the genie out of the bottle. Even if Trump himself ‘only’ has four years in office, the shape of post-Trump US politics and policy is unknown.

In relations with the US, the world now faces policy unpredictability and a lack of clarity, all of which leads to uncertainty – as well as the manifest willingness of the US administration to inflict harm on other countries including those typically seen as being friend/allies. In response, the sensible policy path to pursue in the short run is to try and minimise the impact on one’s domestic economy and attempt to dissuade the US from its actions; and in the medium to longer run to distance oneself (possibly even decouple) from so much dependence on the US. For some countries this will be easier than others, and it is important that countries cooperate and coordinate in their responses to the threat posed by the current US administration. This is the case even if the current swathe of policies appears to get reversed under pressure from businesses and constituents in the US – because who knows what policy may be introduced the next day.

This will not be easy and will take time and the desirable extent of any ‘distancing’ or resilience building is far from clear. That it is needs considering is not. There is also a further major consideration. The US is not simply an economic power, but also a hugely significant military and political power. The interdependence between the US and its allies is far more than just economic. Economic distancing without political distancing is a very delicate balancing act and may well get upended by US actions as well.

In discussing that ‘sensible policy path’ let us not forget that it is firms and businesses who do the exporting, importing and investing. The reshaping of trade and investment flows triggered by these actions will also be driven in good part by the decisions made by the private sector, which tends to vote with its feet. It may be that this will all blow over, but this does seem pretty unlikely. It is more likely that trade and investment flows will be substantially reshaped.

The US is a very big player in the world economy and will continue to be so. If Trump’s policies aim to reassert US dominance, they may have the opposite effect. Regardless, we are in for a challenging period for the global economy.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.