Trump’s tariffs: How much should we be concerned and why?

Written by: Michael Gasiorek, Anupama Sen

With President Donald Trump’s second term, the debate over the use of tariffs is making headlines. On his first day in office Trump once again raised the prospect of the strategic use of these tariffs: he threatened to impose them unless partner countries (Mexico, Canada or the EU) introduced changes in their trade policies or made concessions in other domains (China with TikTok). This approach is likely to have profound implications for both the US as well as on the global economy for three key reasons. First, it will impact the already strained multilateral trading system. Second, there are direct consequences of US tariffs on individual partner countries. Third, there is the question of how effective such actions will be for the US, and that will also depend on the extent of any retaliatory measures.

The UK-U.S. Trade Relationship

Trump has threatened to impose sweeping tariffs—ranging from 10% to 20% on all trading partners, and up to 60% on Chinese imports. These statements clearly cover a multitude of possibilities, and this generates considerable uncertainty. The UK government appears hopeful that as the US does not have a trade deficit with the UK, that the UK may not be targeted. However, this is also uncertain.

Currently, the US does not levy tariffs for many products. Indeed, out of the more than 4000 HS 6-digit products the US imports from the UK in 2023, tariffs are currently zero on nearly 60% of these, and below 5% for approximately for just over another third of products exported to the US, and there are just over 300 products where the tariff is more than 10%. It is not clear if the presumed “10% (or 20%) tariff” would be to increase all existing tariffs by 10 (or 20) percentage points, or to introduce a flat rate of 10% (or 20%) on all products.

There are two issues to consider regarding the impact on the UK. First, what might be the overall impact, and secondly, which are the products or sectors which will probably be affected the most by the change in the tariffs.

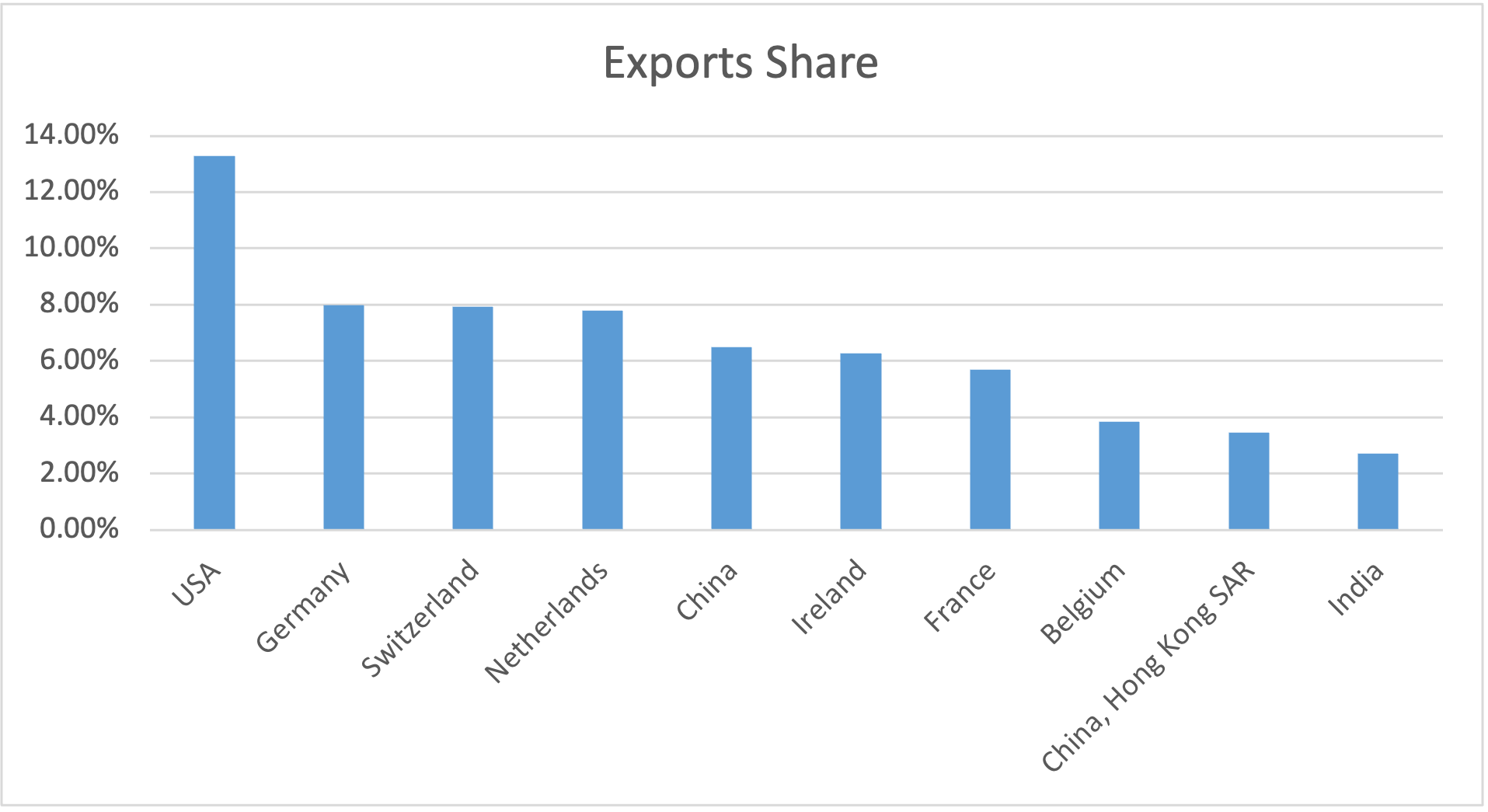

In terms of the overall impact, the US is the UK’s largest single trading partner, accounting for 13.28% of goods exports in 2023 (see Fig 1)[1], and our simulations suggest that the application of tariffs across the board could result in a e £22 billion decline in UK exports in aggregate[2]. Although this is a big number it does represent only 2.6% of the total value of UK exports.

Figure 1: shares out of total UK exports

Source: UN Comtrade, 2023.

Those aggregate effects mask the different impacts on different products and industries. In the simulations referred to above, for instance, certain sectors (fishing, coke and petroleum) experience the largest declines, of over 20%. The size of these impacts will depend on several factors, but key among these will be the share of UK exports in any given product going to the US, the change in tariff which is imposed, and how sensitive a product is to any tariff changes.

In the rest of this blog, therefore, we consider at a much finer level of disaggregation which might be the products or industries most affected by the potential change in tariffs. At the most detailed level of internationally harmonised trade statistics (HS 6-digit), the UK exported 4086 ‘products’ to the US in 2023. Out of these, there are 13 products, ranging from titanium ores to jellyfish, which are only exported to the US: prima facie, these are the products whose exports could be most affected.

Consider Table 1 below. For each HS6 digit product, we calculated the share of exports going to the US as opposed to other destinations. In other words, we measure the export dependency regarding the US. We have done this both for the UK and China. We then identify four groups: those for which the share going to the US is 25% or less, and then those where the shares are 25%-50%, 50%-75% and more than 75%. For each group we report the number of products falling within it, and the share out of total UK exports to the US which those products account for.

Table 1: Export dependency on the US

|

United Kingdom |

China |

|||

| Export Range | No of products | Total Export share | No of products | Total Export share |

| 25% or less | 3424 | 55% | 3654 | 60% |

| 25% to 50% | 501 | 38% | 468 | 38% |

| 50% to 75% | 112 | 3% | 47 | 2% |

| More than 75% | 49 | 4% | 24 | 0% |

Source: Authors calculation using the data from UN Comtrade.

For the UK there are 161 products for which 50% or more of their exports go to the US. We would expect these to be the product most affected by the Trump tariffs and will henceforth refer to them as ‘vulnerable’ products. Note, however, that the total export share of these vulnerable products is only 7%, so while these products may be individually highly affected, the overall impact on UK trade is likely to be small.

The 161 vulnerable products cover a very wide range of sectors. Looking at a more aggregate level the data can be organised into 96 broad industries. The 161 product fall into 52 of these. However, the four chapters with the highest number of such products are: ‘organic chemicals (19 products); ‘inorganic chemicals’ (15 products); machinery (3 products), and ‘fish and crustaceans’ (8 products). It is interesting to note also that out of these products, close to 50 currently do not face any tariffs, only 10 face a tariff greater than 10%, and the highest tariffs is on malt extracts at just over 21%.

The impact on UK exports and producers will also depend in part on the policies Trump may introduce on other countries. For instance, if Trump introduced a 60% tariff on all Chinese exports, as well as a 10% tariff on UK exports, the UK would have better access to the US market in comparison to Chinese firms. This relative effect is likely to mitigate some of the losses for the UK (which was also considered in the simulations referred to earlier), especially considering the large overlap between UK’s and China’s exports to the US. Out of the 161 vulnerable products, there are over 100 that China also exports to the US, and out of all the 4086 products the UK exports to the US, China exports 3461 of these.

There is an important question to consider: How much leverage do the possible ‘Trump tariffs’ really provide to the US? This is difficult to determine because so much is unknown. If we focus only on goods trade, a reasonably strong case could be made that the leverage is not that big, and countries should resist knee-jerk reactions and not be overly worried. While over 13% of UK goods exports go to the US, and simulations suggest that the tariffs could result in losses of £22B for the UK, £22B represents only about 2.6% of total UK exports, and the analysis above suggests that there is only a small fraction of UK exports which are heavily dependent on the US market. While Trump’s actions are concerning, the extent to which the tariffs can be weaponised to induce policy changes in the UK may be limited. This could also be the case for China, as Table 1 shows that products for which the US absorbs more than 50% of their exports are only worth 2% of total Chinese exports, and for 60% of their exports, the share of their exports going to the US is less than 25%. The evidence also suggests that Chinese firms did find ways round previous US tariffs by producing and trading through third countries such as Vietnam and Mexico.

On the other hand, there are additional, more intangible concerns which go beyond the calculations above. While ‘only’ 13% of UK goods exports goes to the US, for services the share going to the US is 27%. To date, to our knowledge, there has been no suggestion by the US administration of interventions here (this may be because the US has a deficit in goods and a surplus in services), but this may not be the case in the future. Another concern might be the future investment decision of multinationals, especially given the recent threats by Trump to increase tax rates on foreign multinationals who may want to align with US policies, and to impose tariffs unless they invest in the US, and the consequent impact on countries including the UK. This highlights that Trumps trade interventions are unlikely to be limited to just tariffs.

While Trump may hope that tariffs will bolster domestic industries, they will also distort global markets, likely provoke retaliatory measures from trading partners, and strain diplomatic relations. While they might protect some industries and jobs in those industries, they will also raise US import prices. This will hurt US consumers, making US firms in other sectors less competitive when buying foreign inputs, ultimately reducing US exports. The tariffs and other policies may inadvertently harm the very consumers and businesses they are meant to protect and will certainly harm America’s standing in the world economic order.

For the UK and other nations, the focus should remain on fostering resilient supply chains, fair trade practices, and the building of strategic partnerships, which are crucial to mitigate the impacts of tariff policies and ensure sustainable economic growth. And in so doing do not readily assume that acquiescing to US demands in response to threatened tariffs is the right response. However, providing a coordinated response may prove challenging, and countries may be tempted to go it alone and strike deals with the US.

Footnotes

[1] Data from UN Comtrade accessed through WITS (World Bank).

[2] https://citp.ac.uk/publications/trumps-tariffs-could-reduce-uk-exports-by-22-billion

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.